Not so very long ago, saying that an artist “had a production line” in their studio was considered an insult: it meant that the work was not growing, and that the artist was methodically repeating something that had been successful in the past. Accusing someone of “phoning it in”, another slam of old, is now a proud way of life for some artists: they are actually phoning art in…. to their fabricators.

Discussions among artists (the only ones who seem to care) regarding the meaning of authorship have come to the forefront in recent decades, due to the skyrocketing auction prices of contemporary artists such as Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Takashi Murakami. These artists have redefined what it means to be an artist as millionaire art superstars, and, not incidentally, they each employ teams of workers to fabricate their designs.

The practice of making art has morphed in response to the art market. When your piece can sell for $23 million, why make only one if the market will buy more and you can have your fabricators make a limited edition of five? A recently released book, The Art of Not Making: The New Artist/Artisan Relationship, by Michael Petry, takes us inside the world of fabricators and the artists who employ them.

While there is nothing new about artists employing assistants, the modern evolution of an artist employing artisans to solve problems and create their work from start to finish is new, and there is something revolutionary about this matter-of-fact book that names names and demystifies the process. This coffee table publication features over 300 color photos of pieces by well-known artists who have hired artisan fabricators to produce their work. Lengthy paragraphs describe the materials and processes used to create each work. The book contains a DuChamp-heavy background essay by author Michael Petry and is divided up into chapters focused on glass, metal, stone, textiles, and “other materials”, with a short introductory/background page for each medium. The book consists mainly of images, punctuated by quotes from artists explaining their philosophies regarding artistic creation, such as Jorge Pardo’s statement: “I don’t think that art gets made with your hands.”

While there is nothing new about artists employing assistants, the modern evolution of an artist employing artisans to solve problems and create their work from start to finish is new, and there is something revolutionary about this matter-of-fact book that names names and demystifies the process. This coffee table publication features over 300 color photos of pieces by well-known artists who have hired artisan fabricators to produce their work. Lengthy paragraphs describe the materials and processes used to create each work. The book contains a DuChamp-heavy background essay by author Michael Petry and is divided up into chapters focused on glass, metal, stone, textiles, and “other materials”, with a short introductory/background page for each medium. The book consists mainly of images, punctuated by quotes from artists explaining their philosophies regarding artistic creation, such as Jorge Pardo’s statement: “I don’t think that art gets made with your hands.”

For me, the most revelatory and thought-provoking part of the book was the section containing interviews with artists who use fabricators, and the fabricators themselves. (Many fabricators are also artists in their own right, and the book includes images of the craftspeople’s own artwork alongside their interviews.) Several interviewed artists refused to reveal who created their pieces, and most revealed that they do not credit fabricators in their exhibitions or sales. Some artists never touch any materials at all, while others make the bulk of their own work and only employ craftspeople when the scale gets too big, or when they think an artisan could do it better.

In one interview, Sam Adams, a London fabricator who works for Jeff Koons and Glenn Brown, was asked, “What would you do if an artist wants you to make something that you feel won’t work?” and he replied, “It hasn’t happened yet. People come to you for solutions – they can start with an outline or a sketch for an idea and we try to put flesh on it. That’s our role in their practice – to make solutions.” When asked a bit later if he would ever employ anyone to fabricate any of HIS works, Adams responds that, in theory, he would, but, “There is a strong link between the thinking and making processes in my work… when I make something… I think about it and maybe I just chop something off here or change something there. You can’t do that if you have someone making it for you.” And this is one of the essential questions one is left with after reading this book that presents fabrication as just another genre of work, with no implications whatsoever: what kind of art is going to be made when artists are no longer solving their own problems or immediately responding to their materials?

As someone whose brain works more like Sam Adam’s than Jeff Koon’s, I found this book fascinating, and read it in one sitting. The possibilities presented are inspiring to artists who might have never considered working beyond their own individual skill set. Despite a rather extensive section on Further Reading, the book could use essays by other contemporary critics and/or curators. I was longing to hear someone ask the questions that, to me, seem to arise naturally from this thought-provoking book and the increasing normalcy of this practice:

Should more art schools (some already have) move away from practical/technical skills? Are there essential qualities of artwork lost when the artist’s body is removed from all but the signature? Are new artists going to be marginalized by artists who have the money to buy better artists to make “their” work for them? The Art of Not Making is a solid landmark in the march towards real transparency and evaluation of previously taboo subjects, forwarded in recent times by gallerist Ed Winkleman’s blog, and Jerry Saltz in his New York Magazine column, and by discussions amongst art world members on Facebook pages. The most successful artists currently using fabricators are Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. Koons comes from a business background and Hirst hired a sideshow promoter to be his manager. Is the real “art” to be found in the marketing and branding? If so, how does this art differ from a Limited Edition Bugati automobile or a Louis Vuitton bag? Some relate artists who use fabricators to film directors, who should never be expected to produce a product single-handedly. But movie directors credit those who contributed to the creation of the work. Is it time to change standards in the art world and ensure that fabricators receive production credit?

Kate Kretz earned a certificate at The Sorbonne and a BFA at the State University of New York at Binghamton before receiving her MFA from University of Georgia. Her work in varied media focuses on human vulnerability as defiant act. Kretz was trained as painter, but her work has expanded to include a line of Psychological Clothing and intricate embroideries made with human hair. Kretz’s work has appeared repeatedly in The New York Times and has been featured in ArtPapers, Surface Design, Vanity Fair Italy, ELLE Japon, and PASAJES DISENO magazines. Her controversial painting “Blessed Art Thou” was reproduced in hundreds of international news sources, was recently included in the documentary, “The Second Tear: Kitsch” for NDR/arte German Public Television, and continues to be published in university textbooks worldwide. Exhibitions include the Museum of Arts & Design, Van Gijn Museum, Kunstraum Kreuzberg, Wignall Museum, Katonah Museum, Lyons Wier Ortt Gallery & 31Grand Gallery, Fort Collins MOCA, Telfair Museum, Fort Lauderdale Museum, and the Museo Medici in Tuscany. She has received the NC Arts Council Grant, The South Florida Cultural Consortium Fellowship, The Florida Visual Arts Fellowship, and a Millay Colony Residency. After working as an Associate Professor and BFA Director at Florida International University for ten years, she recently moved to the Washington, DC, area. Kretz continues to teach as a visiting artist at various universities and works alone in her studio on obsessive pieces that can take up to 12 months to complete. She has always believed that the personal life hours invested in her work are part of the gift given to the viewer. Kretz could never make the bent wood sculpture stand upright in her undergraduate 3D design class, but has always wanted to be a sculptor, and is therefore very intrigued by this fabrication idea. Her work can be seen at www.katekretz.com, on Flickr, and Facebook.

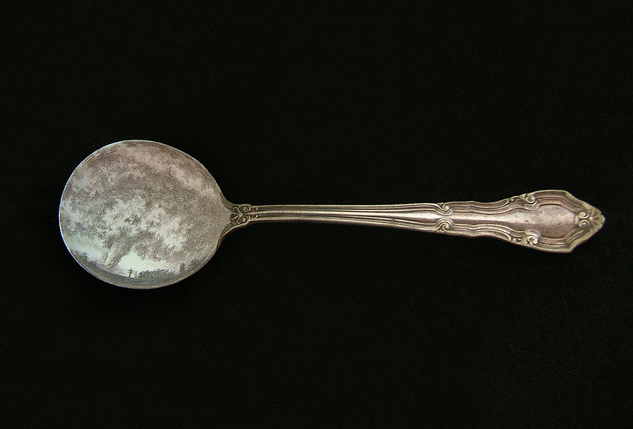

Images in this post all by Kate Kretz:

“Tempest”, 2011, tarnished silverpoint on found spoon, 1.5 x 5.5 x 1″

“Crying Man” (detail), 2005, acrylic & oil on masonite, 24 x 18”

“Special Angel”, 2010, etched mirror, graphite, paper, 20 x 16″ oval, from an ongoing series of guardian angels who don’t come through.

There were other questions we did not have room for:

Is art making, like everything else in our society, following the profit-motivated corporate model of outsourcing? Are the “independent businesses” of single artists going to be pushed aside by those artists who have the money to make more money?

Art used to be a democratic practice: if you were born with talent, you simply needed the time and some humble materials to create great art. How can the most exciting painting compete with the kind of spectacle that can be produced by an army of skilled artisans and an unlimited budget? Is contemplative, meaningful work going to be subsumed by art with the scale and man hours “wow” factor? (i.e., who’s ready to volunteer to hang their powerful but quiet drawing in a show next to “Puppy” in full bloom?….)

I see this in the dance world… everything is getting more and more gymnastic. More like cirque d’soleil. The line between athletics and dance/art is blurring.

After reading this, I sat for a while and tried to imagine being so rich and connected, I could make (or have others make) any kind of art I wanted to be made. It is hard for me to even conjure up the dream. I too think like you and Sam Adams. “Process over product” is the foundation of my art being. Also, I am so far out of the Hirst/Koons league, I hardly see any kinship at all.

You ask “what kind of art is going to be made when artists are no longer solving their own problems or immediately responding to their materials?” The answer is right before our eyes and filling all the rooms at the Whitney right now (Jeff Koons Retro). I don’t see this going away either. I just see it becoming more prevalent and acceptable. Perhaps, it will become expected.

I watch art videos every day. Recently, I have been taken aback by artists of far less “status” using assistants to make their art. As the artist stands back and speaks to the camera, an anonymous crew of college age artists are behind him/her painting away. It makes me cringe.

Most artists are already marginalized. There are many art “worlds”. There will always be artists who single-handedly make those quiet drawings. However, those drawings will be seen in other places, not next to “Puppy” in full bloom”. I am not sure this is such a bad thing either.

Showing this kind of mass produced art, the MOMAS and Guggenheims all over start to become as predictable and boring as all those big malls with the same chain stores showing the same products in Barcelona or London or or NY… Sometimes the most interesting products are found in small shops in those cities, creative handmade clothes and shoes and stuff. Also, a stroll around secondhand shops or junkyards is often aestheticaly more rewarding for me, than visiting many contemporary art museums.