Do you know how small a book of hours actually was? Well, they could be pretty big, some of them, but I’ll tell you right now that the majority of them fit right in your damn hand like it was an iPhone. You stuck the thing in your pocket, you carried it around, and it told you what prayers you were supposed to say at a certain hour. Or, rather, it was supposed to tell you what prayers you were supposed to say, but at a certain point the people who were buying these things got carried away with their cash, and started asking for more gold-leaf and different writing, and compliments to the patron, and calendars, and pretty pictures and different stories and fancy allegories, and, y’know, you get the idea.

That’s the point where the book of hours ceased being a simple devotional script and turned into a sort of intellectual repository, not just for the person whom it was made for, but for the artist writing and painting in it. These books were, in some sense, an attempt to swallow everything: everything the buyer loved would go in there, their recipes, their favorite stories, pictures of their family members, their personal philosophies. Everything. But always, in the background, there’s somebody else watching things, doing the grunt work, and inserting their own ideas and suggestions as bizarre notes and pictures in the marginalia. Is this starting to sound like Facebook to you?

Either way, this is the jumping-off point for my work. When I became (became? Is that really the right word?) an artist, I started with a completely different goal: I would write and draw fun comics that lots of people would be interested in reading, and do some paintings that would be like public statements or something stupid like that. Unfortunately (for the world, not for me) the advice I always got regarding art was to make what you wanted to see in the world. And so I did. And I began to see that what I wanted to see wanted to see me too, and that it had a story of its own to tell. (Oh my god, I do sound completely nuts)

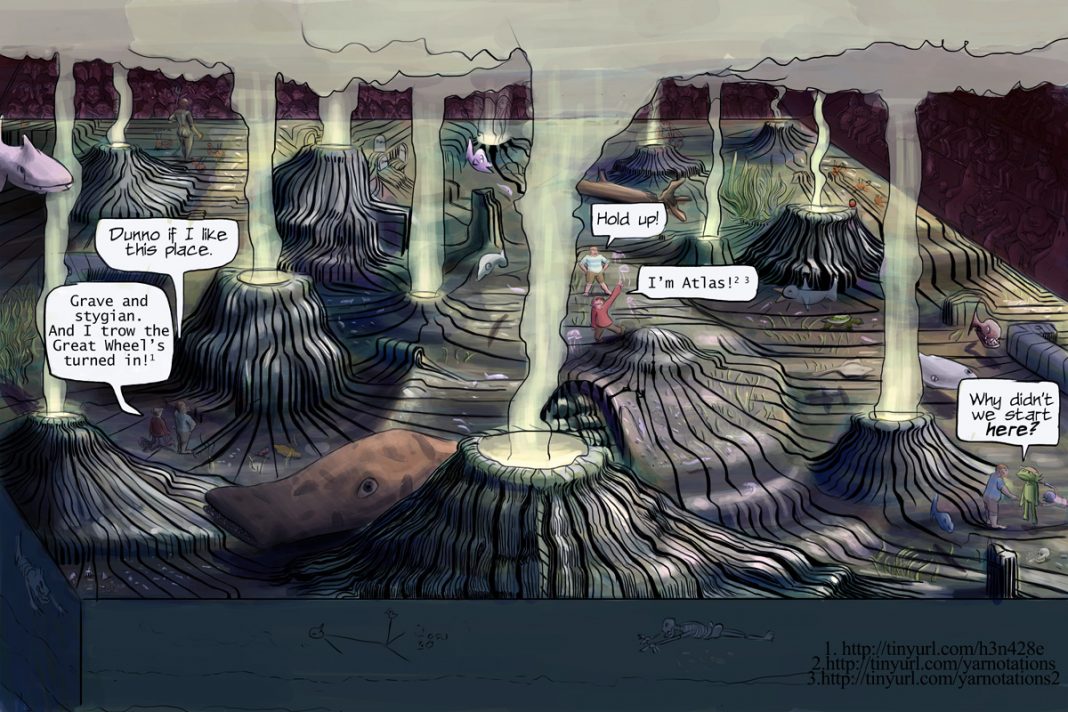

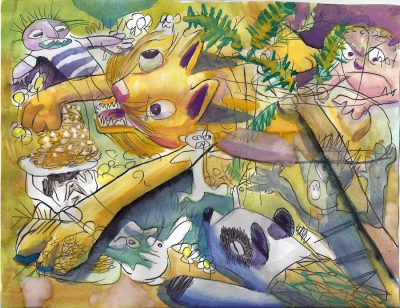

So, my works are less like individual paintings and more like pages from an illuminated manuscript. Or a book of hours. Whatever I said earlier. Yes, they can function outside of the context of the other pieces, but they are really only truly alive within the environment created by their neighbors. I would say this is because they are birthed within the context of the other works produced, and fueled by the turns in the narrative around them. Each painting is a small theater in which the characters are allowed to act any way they want, and their stories begin to drive the production of the work. It’s a process that started with my comics. Things start out one way, and transform into something different.

Right now, I’m working with Batboy. The series didn’t start out with Batboy. It started with evil frogs, but now it’s Batboy. Batboy first appeared as a sensationalist (and self-aware) lie in the Weekly World News Periodical, and he is a character who is connected to things I am very much interested in: the intersection betwixt fiction and reality (Fake News), the use of archiving techniques (he has his own family tree, check Wikipedia), the character (the concept) shared by multiple writers, self-referential jokes, bad puns (again, check the family tree); he was even born in the same place as myself (West Virginia, though he was born in Hellhole Cavern). Throughout the process of making these works the connections have become apparent, and Batboy (as I see him) has taken on a life and a character that I’m simply watching now.

But that’s just Batboy, you know.

There are also Greek Orthodox Churches. When you step into a Greek Orthodox Church it’s a powerful moment, even when there are lots of obnoxious tourists around who’ve been forced to wear makeshift skirts because they weren’t smart enough to wear real pants like a grown-ass adult. But in those churches, you’re surrounded by pictures, steeped like a human tea-bag in art. And it’s absolutely fantastic. The pictures in those buildings aren’t like the frescoes in the Sistine chapel or in a museum. They’re not there waiting for you to stare at them. They’re waiting to stare at you. And when you walk in there, with those magnetic eyes pulling you in every direction, you realize (if you’re like me, I suppose) that you’ve walked into a space designed by someone who wants you to live inside of these stories, to place you inside the protective confines of a story, in order to have a moment of peace and contemplation. They’ve constructed a room that functions like a book.

I don’t like living in a small apartment because there’s not enough room for my paintings, and when I have to store them somewhere else it makes me sad that I won’t be able to see them. I want to have that room for myself and for others; I want to construct it, and then take it apart again to see what it’s made of. I want, like one of Brueghel’s contemporaries said he did, to swallow the world, and spit it back out to see what I can make of it.

So I’m moving to Buffalo.

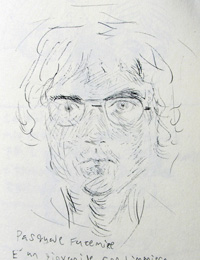

Patrick Facemire started drawing in high school because he wanted to make comics, was unable to get any of the lazy bastards in his school to do it for him. He went on to receive his BFA from Shepherd University, is currently volunteering with Americorps for the Mountain Arts District, and will soon be pursuing his Master’s degree in Fine Art (in Buffalo.) His work revolves around the interplay of narrative, systems of information, and the interactions between space, time, character and theatre. He is obsessed with Tom Waits, cartoons, and books, and you can see his work and read his comics at https://sittingpreamble.com, or you can follow him as @patrickfacemire on Instagram.

Patrick Facemire started drawing in high school because he wanted to make comics, was unable to get any of the lazy bastards in his school to do it for him. He went on to receive his BFA from Shepherd University, is currently volunteering with Americorps for the Mountain Arts District, and will soon be pursuing his Master’s degree in Fine Art (in Buffalo.) His work revolves around the interplay of narrative, systems of information, and the interactions between space, time, character and theatre. He is obsessed with Tom Waits, cartoons, and books, and you can see his work and read his comics at https://sittingpreamble.com, or you can follow him as @patrickfacemire on Instagram.

This article was created as part of the BloomBars: imPrint project, a publication series connected to an exhibition at the Gallery at Bloombars April 14 – May 5, 2018.